Andreas Gursky show reopens the Hayward Gallery in style

The Andreas Gursky retrospective at the Hayward Gallery is a fitting exhibition to mark today’s reopening of this landmark London venue

The large-format work of Andreas Gursky and the newly renovated Hayward Gallery on London’s Southbank seem made for each other. The German photographer’s images have the size and power to fill the considerable space, while the grey concrete and white walls of the reopened Brutalist gallery provide a suitable container for his supersized pictures.

As Hayward Gallery Director and the show’s curator Ralph Rugoff said in his introductory speech at the press view, the reopened gallery is as much about conjuring “surprise” as anything. And the wider intent is that this is exactly what the art should be doing within its walls as well.

This retrospective of 40 years of Gursky’s work certainly achieves that. While it features some of the gigantic images that have made his name, there are also several pieces that reveal different approaches in his photographic practice, even if they address themes that have recurred throughout his career.

The opening room displays an early series that Gursky started in the 1980s while under the tutelage of conceptual photographers Bernd and Hilla Becher. Large images of the natural world – and of people dominated by these outdoors settings – reveal the mark of the industrial footprint, too. In Ruhr Valley (1989), Gursky’s camera is positioned so that the vast bridge in the picture blocks out a solitary tree with one of its huge pillars. In Mülheim, Anglers (1989) – shown above – a distant bridge spans and interrupts the waterside landscape.

Gursky has moved further into an investigation of the industrial process as both his work and the culture itself have developed, taking (and often making, through composites) images of some of the most dominant socio-political forces in late-20th and early-21st century life, be they via abstract close-ups or detached overhead shots.

For example, Untitled I (1993) is a close-up of a section of a grey carpet in the Kunsthalle Dusseldorf gallery – but at first glance it has the haze of a screen full of static or a field of neat crops shot from a plane. It’s banal but disconcerting. A similar trick is employed in a beautiful photograph of some ceiling lights taken at the Assembly Rooms in Brasilia (1994).

When the subject of a picture is seemingly more straight-forward there are still plenty of interesting ideas at play. Gursky’s image of the Tokyo stock exchange, for example, taken high up above the trading floor, shows an abundance of colour in the different jackets the traders wear. Despite – or because of – the sheer number of elements in the image, there is no single focal point, nothing is individually singled out for attention.

Gursky’s famous 99 Cent (1999) photograph of the interior of a 99 cent store, shelves chock-full of products, is a riot of packaging, logos and type. Consumers are present in the aisles but they are dwarfed by the goods around them. It looks hyper-real and is, in fact, a composite made up of a number of different viewpoints – creating an impossible perspective – with the photographer manipulating colours and adding in ceiling reflections.

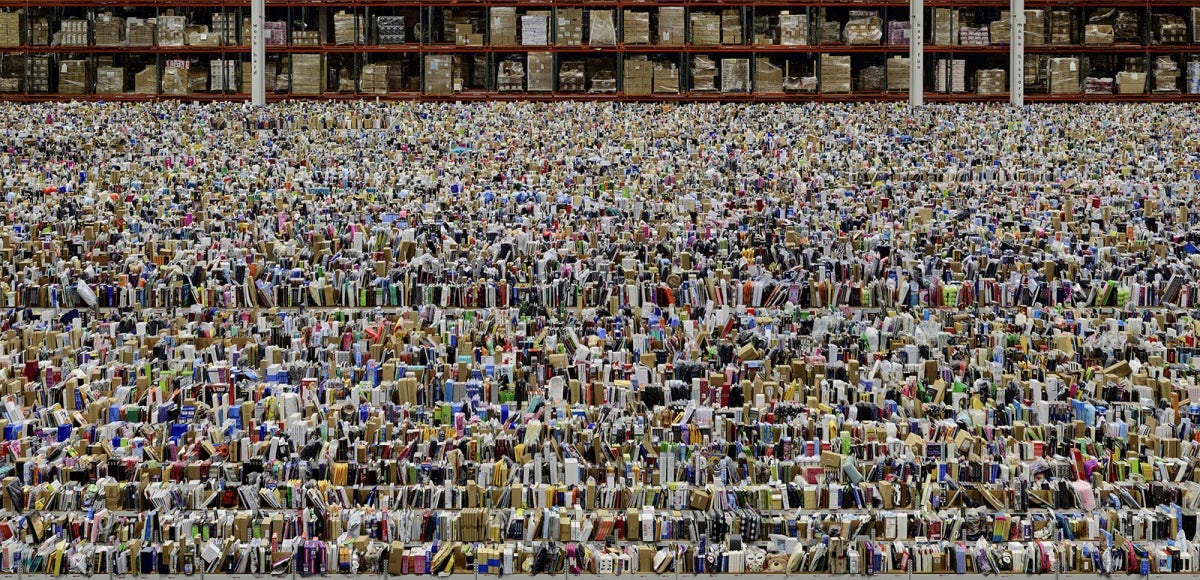

In what feels like a particularly potent image of our time, Gursky’s recent photograph of the interior of an Amazon depot (above) reveals an array of products stacked on endless shelves. While it looks disordered, the hidden digital systems at work here know exactly where everything is – there is a strange, silent order to this apparently chaotic picture.

The scope of subjects here is, unsurprisingly, vast – and Gursky takes in capitalism, environmentalism, consumer culture, globalism et al. There are stunning images of buildings and man-made structures alongside depictions of Antarctica (in its entirety) and the Atlantic Ocean, constructed from satellite images.

Of his recent work, Gursky’s use of the smartphone camera once again enables him to play with ideas of size and scale. A familiar experiment that many of us will have done while on a moving train or in a car is to take a picture out of the window: Gursky’s version (above, on left), taken while travelling on a road in Utah, is displayed at an extreme size and is one of the only images in the exhibition that relishes in showing movement.

It certainly feels like one of those surprising moments that Rugoff made reference to in his speech. In this setting, Gursky’s enormous works are given plenty of space to breathe and there are surprises around every corner.

Andreas Gursky is at the Hayward Gallery until April 22. See southbankcentre.co.uk