Fully Exposed

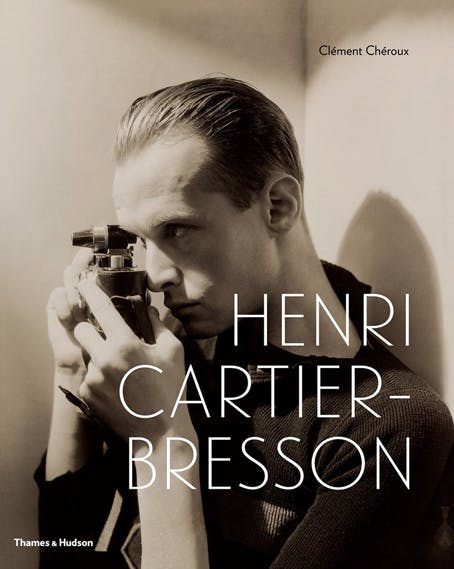

Ten years after his death, the great photographer Henri Cartier-Bresson is the subject of a comprehensive retrospective at the Pompidou Centre in Paris revealing many hitherto ignored aspects of his work. In an exclusive interview with CR, the show’s curator Clément Chéroux discusses Cartier-Bresson’s career and enduring relevance

Ten years after his death, the great photographer Henri Cartier-Bresson is the subject of a comprehensive retrospective at the Pompidou Centre in Paris revealing many hitherto ignored aspects of his work. In an exclusive interview with CR, the show’s curator Clément Chéroux discusses Cartier-Bresson’s career and enduring relevance…

CR: Why this retrospective, why now?

CC: It’s been eleven years since the opening of the Fondation Henri Cartier-Bresson, ten years since the photographer’s death. It was finally possible to put an in-depth perspective together based on the archives and to place Cartier-Bresson’s work as a whole into an historical perspective.

CR: How long did it take to put together?

CC: Three years.

CR: As director of photography at the Centre Pompidou, curator of this monumental exhibition and author of its catalogue, you have devoted a great deal of your life to Henri Cartier-Bresson. What is it about him that fascinates you?

CC: The quality of his compositions, but also his great intelligence in understanding situations. Wherever he went, Cartier-Bresson instantly understood what was important, what was newsworthy. Above all, he had an immense talent for communicating a complex situation visually.

CR: This exhibition of over 500 photographs, paintings, sketchbooks and drawings, provides an intricate and complete portrait of the photographer. It retraces his lifetime’s work in depth, breaking away from the stereotypical image of Cartier-Bresson. Was this your intention?

CC: Yes, it was exactly that. Breaking away from a certain ‘mythology’ of his work guided me in my research and in taking my curatorial decisions.

This exhibition shows that there is not one, but several Cartier-Bressons. In his 70-year career, he was not always the same person. From Surrealism to Buddhism, Communism and Humanism, he traversed the majority of the greatest ‘isms’ of the 20th century.

CR: How does this retrospective differ from previous exhibitions of Cartier-Bresson’s work?

CC: Most of the previous Cartier-Bresson exhibitions sought to present a unified vision of his work. At the Pompidou Centre exhibition, we’re showing the very different periods of his career distinctly. Previous retrospectives tended to be thematic. The geographic approach was frequently explored – India, America, Europe. We substituted this geographical approach with an historical one. This retrospective retraces Cartier-Bresson’s career chronologically from the 1920s up to his death in 2004.

CR: Cartier-Bresson left an enormous, meticulously filed archive. In the course of compiling this exhibition, did you make any discoveries or find unknown work or information that caused you to revise your knowledge of him?

CC: Yes. The work of the whole pre-war period which corresponded to Cartier-Bresson’s engagement with communism was previously undiscovered. His Magnum years, from 1947 to the start of the 1970s were also only partially understood. The whole of Cartier-Bresson’s work on the subject of some of the major problems facing the latter half of the 20th century – I’m thinking principally of consumerism here – have never previously been seen. Therefore, a great deal here remains to be discovered and understood.

CR: For this exhibition, you took the decision to print Henri Cartier-Bresson’s photographs to the scale he originally printed them. This occasionally makes for surprising viewing – some of the prints are the size of a pack of cigarettes, details are compressed or even lost. Why was this important to you?

CC: Up to the time of his death, all of the European exhibitions printed Cartier-Bresson’s photographs on the same type of paper in only one or two formats. The result was a great uniformity of image. In the Pompidou Centre exhibition, we’re displaying only the prints of each specific epoch, so that we have a better perception of the photographer’s evolution.

In 1939, on the eve of the outbreak of war, Cartier-Bresson destroyed many of his negatives. Many of his photographs inspired by Eugène Atget, photographs of his trip to Africa from 1930-1931 and some of his Surrealist images no longer exist other than in the form of these original prints made before this destruction. It would have been a great pity not to have exhibited them.

CR: This exhibition debunks several ‘myths’ about Cartier-Bresson, for instance that he only used a 50mm lens, he never cropped or reframed his photographs, he never used a flash, he never worked in colour, he never retouched his prints, his whole philosophy can be neatly summed up by the phrase, ‘the decisive moment’. Was this deliberate?

CC: Most of the misconceptions or ‘myths’ relating to Cartier-Bresson’s work date from the end of his life, a time when it was particularly under media scrutiny. But he didn’t always defend the same viewpoint. His surreal photography from the early 1930s is very different to his post-war photojournalism. The historical approach advocated in this exhibition puts these myths back in context.

CR: The major photography awards have been dogged by controversies over photographers retouching images recently. Was Cartier-Bresson’s position with regard to retouching as purist as we might think?

CC: Cartier-Bresson used retouching at the beginning of his career in the 1930s. However, at the end of his life, he was violently opposed to it.

CR: He photographed in colour with reluctance, succumbing to pressure from magazines such as Life, Jours de France and Paris Match. “This was a matter of professional obligation, not a compromise but a concession”, he stated; colour photography was “a means of documentation, not of artistic expression.” He was dissatisfied with the results of his colour photography. What is your opinion of his work in colour?

CC: This is yet another example of the contradiction between what Cartier-Bresson did between 1950 and 1970 and what he said about it afterwards. This shows the necessity, in the context of an historian’s approach, not to stick too closely to the artist’s discourse or to the clichés circulated by his commentators, but to focus on the archives of his work.

CR: On assignment at the coronation of King George VI for Ce Soir magazine in 1937, Cartier-Bresson turned his back on the royal procession and shot the spectators instead. Only one image of the royal carriage was found in the archive of this commission. It was quite a daring and humorous thing to do. His editor may not have been amused. Was humour an important aspect of Cartier-Bresson’s vision?

CC: Yes, humour is a very important dimension in his photographs of the 1930s. At that time, his communist commitment was also a very important factor. While reporting on the coronation of King George VI, turning his back on the king to photograph his subjects was also a highly political statement. We can see something profoundly revolutionary in Cartier-Bresson’s reversal.

CR: You have stated in an interview [with Jeanne Fouchet-Nahas for Connaissance des Arts] that the shot of spectators holding up home-made periscopes to catch a glimpse of King George is one of your favourite images of the exhibition – why?

CC: Precisely because of its political dimension.

CR: Do you have another favourite?

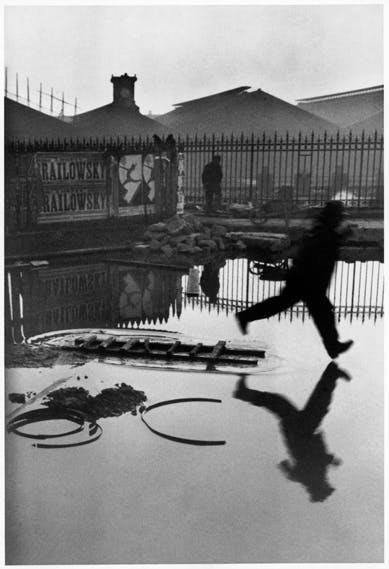

CC: I love his photograph of the man jumping over the puddle behind the Gare Saint-Lazare. It’s the perfect illustration of the ‘decisive moment’.

CR: Cartier-Bresson was very attracted to film making, but made only six films in all. His collaboration with director Jean Renoir lasted four years before the outbreak of the Second World War. Was he frustrated by the medium or by the result?

CC: Cartier-Bresson sought to make films at the time of his engagement with communism because he felt that films “spoke to the people” and enabled him to communicate his beliefs to them. After the war, he was too immersed in photo-journalism and in creating Magnum [Cartier-Bresson was a co-founder of the agency in 1947] to have a parallel career as a film director.

CR: Cartier-Bresson owed part of his ‘living legend’ status to being in the right place at the right time. He was the first western photographer to enter the former USSR since 1947, he was with Gandhi three hours before his assassination and reported on his funeral. Was this luck, genius or foresight?

CC: Frequenting the Surrealists gave Cartier-Bresson a taste for hazard. But he was also endowed with a great intelligence for situations that allowed him every opportunity to seize this chance.

CR: You place strong emphasis on Cartier-Bresson’s political beliefs and activism. This provides a key to a great deal of his work, particularly in cinema, with his film, Victoire de la Vie, his first anti-fascist political film. Was this your intention?

CC: Activism is too strong a word, I would rather say political engagement. Like many young people of his generation, Cartier-Bresson chose communism primarily as a means to stop the rise of fascism.

CR: Cartier-Bresson was many things in the course of his career – surrealist artist, photographer, moviemaker, reporter, photojournalist, co-founder of Magnum Photos, a visual anthropologist, and, towards the end of his life, once again a photographer and an artist. Which was his most successful incarnation to you?

CC: They were all successful to varying degrees. As an historian, I’m most interested in his communist period. As an art historian, I prefer his Surrealist period. And as a photography historian, I find his photojournalism period passionately interesting.

CR: How relevant is his work today? What lasting imprint has he left on photography?

CC: Photography is now fully recognised as an art form. This is no longer Cartier-Bresson’s role. He was the first model for a whole generation of photographers, then he became the ‘anti-model’ to those who followed. Today, he has earned his place as one of the greatest artists of the twentieth century, with its periods of predilection based on individual taste.

CR: In a review for the Financial Times, Francis Hodgson wrote; “Cartier-Bresson’s time as the great yardstick of photography has passed….This massive show, so scrupulous in its rounded view, marks that passing.” Do you agree?

CC: Yes.

CR: What do you think Cartier-Bresson’s motivating force was as a photographer?

CC: As he always said, his motivation was “la vie”.

CR: This retrospective is simply entitled “Henri Cartier-Bresson”. If you were to add a subtitle, what would it be?

CC: The exhibition could have been entitled “Henri Cartier-Bresson, Here and Now” because it doesn’t show a man frozen in time, rooted to the spot, like a statue erected to his legend.

This Cartier-Bresson travels the world, discovers other cultures, encounters very diverse people, traverses several epochs and actively participates in some of the greatest intellectual movements of the twentieth century. This is a Cartier-Bresson in his own context, forever defined by the ‘here’ and by the ‘now’.

Henri Cartier-Bresson is on until June 9 at Centre Pompidou, Paris. See centrepompidou.fr. An accompanying book (cover left), Henri Cartier-Bresson: Here and Now, written by Clément Chéroux, is published this month by Thames and Hudson, £45