The lost legacy of the Chinese movie mag

Film magazines played a pivotal role during China’s movie industry boom, but fell into obscurity after the 1950s. A new book from Thames & Hudson explores their visual and cultural impact

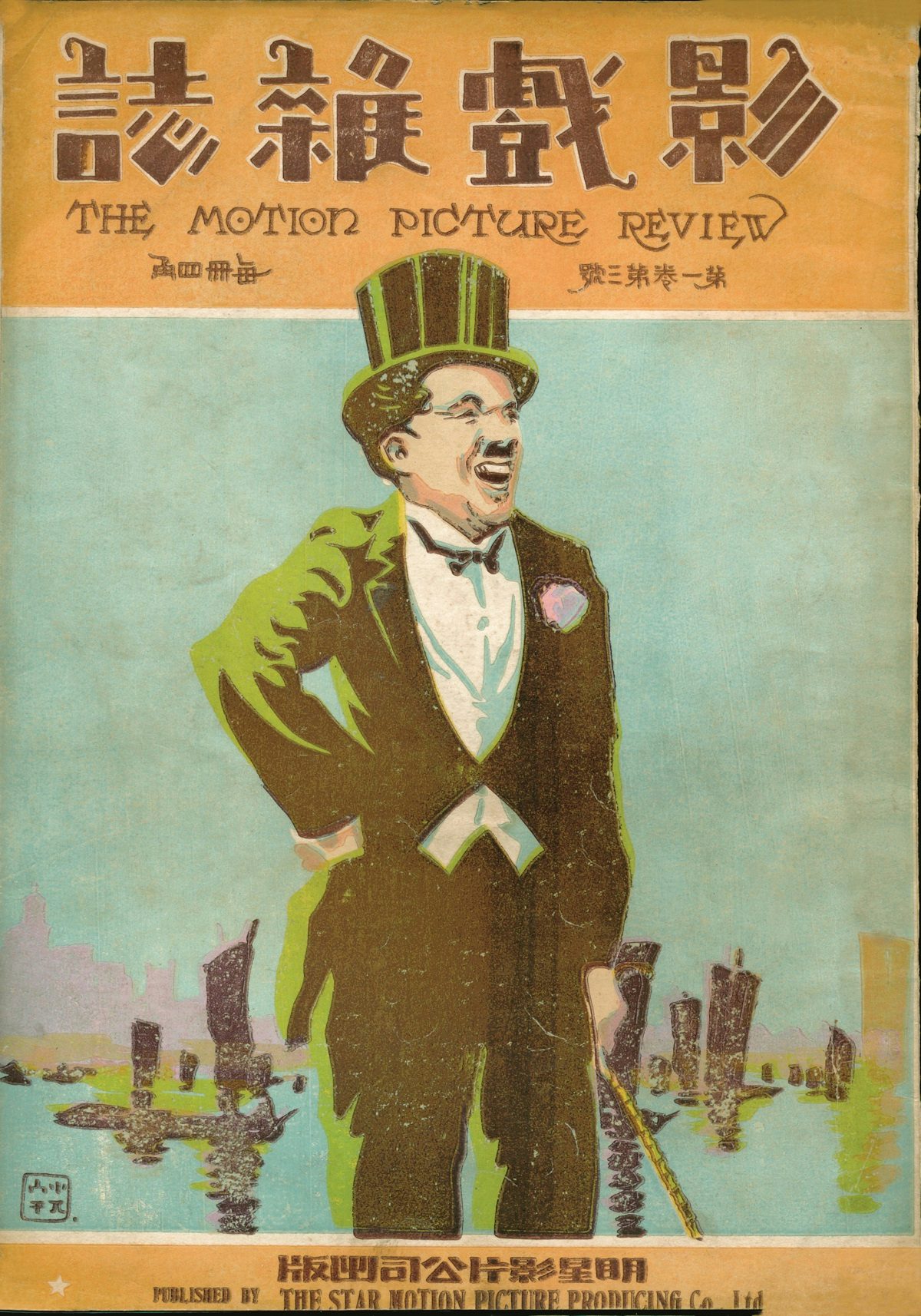

Chinese Movie Magazines, by Paul Fonoroff, draws on the author’s own personal collection of film publications – one he says rivals many of China’s own archives. Hundreds of magazines are featured in the book, which traces their evolution from the earliest days of the country’s movie industry, through political and social upheaval, and into their final demise under Chairman Mao.

Movie mags developed rapidly in the 1920s, when studios began opening in China and the country saw its first feature films. While Shanghai was earning its name as the Hollywood of the East, publications sprung up, some independent, and some released by the city’s large concentration of movie theatres. These magazines celebrated Hollywood productions as well as Chinese releases.

Often, a lack of budget meant they substituted photos with etchings, giving rise to some beautiful imagery. This is particularly evident in The Movie Guide, which used Art Deco sketches created by brothers Wu Guchan and Wan Laiming – who would go on to earn the title of ‘China’s Walt Disney’. The book’s author notes that, in some instances, artworks were even given their own titles on the cover – “a fact perhaps reflective of the increasing critical esteem afforded such illustrations and their creators”.

At times, cover artists also reflected on the wider context of the time, such as The Movie Weekly, which in 1931 responded to a nationwide ban on wuxia action films with a cover that depicted knights defending a burning fortress.

As the publishing industry entered the 1930s, photographs became more common, and magazine covers often focused on popular actresses such as Butterfly Wu and Ruan Lingyu. Their influence continued into the 40s, but by the 50s the Communist takeover spelled the end for film studios and independent movie mags. The change is evident in magazines that date back to 1950, which no longer treat cinema as a celebrity driven culture, but rather propaganda for the ruling party – evident in the covers that featured Chairman Mao.

Fonoroff notes that there’s now “little trace” left of the magazines’ influence, with many readers lacking the room to keep periodicals, and encouraged to let go of these “relics of a reactionary past”. Luckily, the writer started amassing his own library of them in the early 80s, collecting mags from derelict theatres, flea markets and second-hand shops – where they appeared as the official attitude towards them became more accepting.

His book – while lacking much detailed design commentary – is a rich source of imagery, and shows the developing graphic culture of these publications alongside political and historic milestones, as well as the changing fortunes of China’s film industry.

Chinese Movie Magazines is published by Thames & Hudson; thamesandhudson.com