Why is 90s cinema overlooked?

BFI Southbank’s new film season celebrates the 90s, which remains one of the most under-appreciated decades in cinematic history – even though it produced some of the most defiant, political films of our time

Whether classic Hollywood or new wave, silent era or 70s sci-fi, many of cinema’s most memorable movements are tied to a certain chunk of history. But where’s all the love for the 1990s? In a new season celebrating the ‘forgotten’ decade, the BFI Southbank is digging up both well-recognised and under-appreciated gems of 90s cinema, and toasting the Young Cinema Rebels that unsuspectingly carved out a new throne for indie cinema.

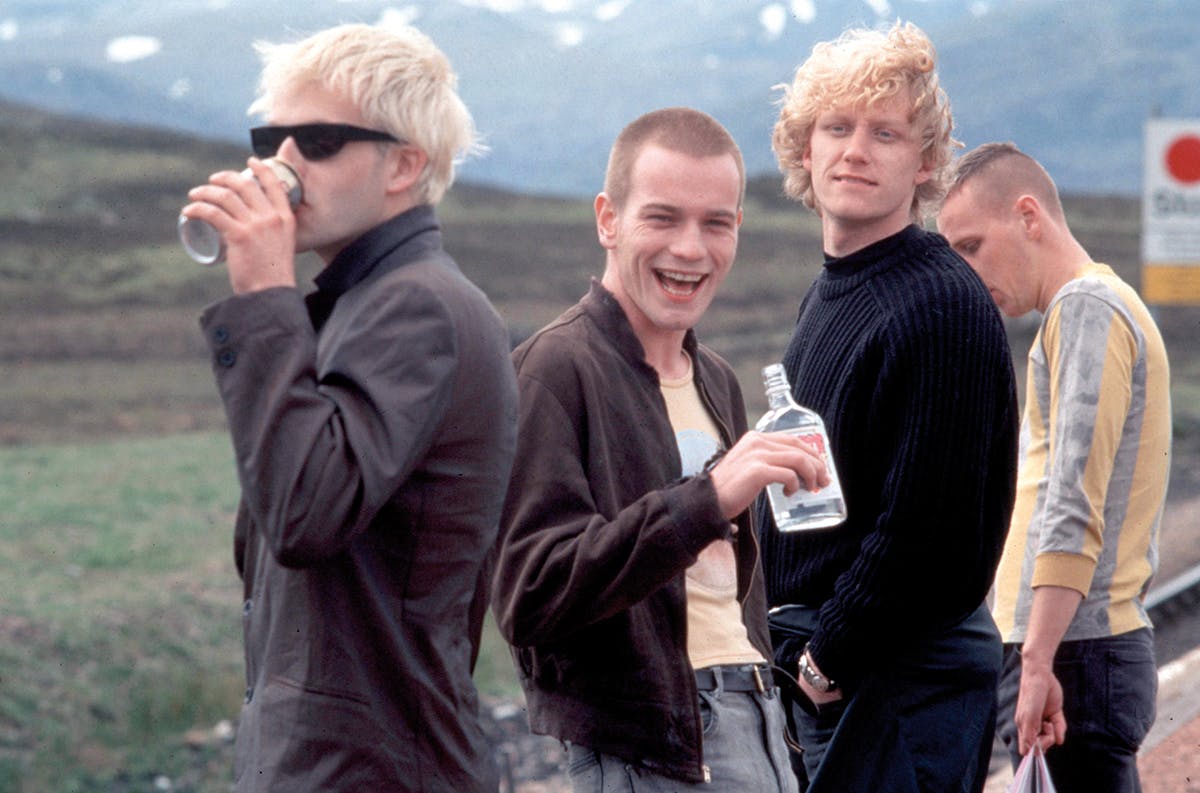

Ninetines: Young Cinema Rebels runs at BFI Southbank throughout July and August, featuring talks and screenings of some of the most pivotal films that came to fruition over the ten years running up to the millennium. Among them are a handful of more mainstream hits like Reservoir Dogs, The Matrix, Trainspotting, and Do The Right Thing, as well as a myriad of lesser-known films to discover.

“The main point of the season is that it’s not a ‘best of 90s cinema’ [season],” explains Anna Bogutskaya, film and events programmer at BFI. “It’s sort of a focus on the filmmakers and the types of stories that were breaking through in that decade, and could only exist between ’89 and ’99.”

“We’re talking about breaking through in terms of the types of people that were making films,” she tells CR, citing the likes of Richard Linklater, Kevin Smith or Quentin Tarantino as filmmakers who were “making films on a shoestring and jumping into the mainstream”.

However, the 90s were also an important time for broadening cinema’s horizons, both geographically and topically. “Even if you go a little further out internationally, Takeshi Kitano was a really famous comedic actor, and then he started making these really dark, violent gangster films that were not expected of him. Or if you think about queer cinema, and Cheryl Dunye or Guinevere Turner, who are making very low budget films about stories that haven’t been seen on screen before,” she says.

These filmmakers have been dubbed Young Cinema Rebels for their admirable sense of impatience. “It’s rebellious in the sense that they were not waiting for the system and the industry to allow them to make their stories and to put them on screen – they’re just going out and doing that,” she says. “That was also extremely of the moment because of the lowering production costs, so they could actually film stuff quite cheaply. They could just go ahead and do it. That’s how you’ve got amazing, influential films like Go Fish, like Clerks, like Slacker, Sex, Lies and Videotape….”

It’s this accessibility that blew filmmaking wide open in the 1990s, and also led to what Bogutskaya calls “canonless cinephilia”, referring to the way that video stores were changing how “people – especially filmmakers – were accessing film. They were not necessarily being prescribed what’s high-art, what’s ‘proper cinema’, what’s low-brow cinema,” she explains.

“They were discovering films on their own terms, on a video shelf in a video store, meaning that they could then create their own cinematic language, drinking up elements from different types of films. Tarantino’s obviously the best example: someone who grew up surrounded by videos and took very specific elements from exploitation cinema, and Hong Kong cinema, and stuff that is not necessarily considered high-brow and wouldn’t be part of the canon, but that they still found something worthwhile in, and that’s reflected in the sort of stories that they would go on to tell.”

With such a rich pool of boundary-pushing films from this decade, it’s strange that more attention isn’t paid to the 90s – something Bogutskaya partly attributes to being generational. “I think it is because it’s too recent, and the people that are in charge of curation and exhibition and distribution don’t necessarily have the distance from that cinema to properly present it. So that’s one element.

“Then I think that because it is so recent, everybody has a very personal take and memory of 90s cinema,” she adds. “You can instantly think of the most amazing art house world cinema or the big American blockbusters that were everywhere. Or you can think of the 90s indie explosion. There’s just so many different variants and entry points into 90s cinema that it becomes really difficult to encapsulate or difficult to define – which is kind of the beauty of it, and it’s what I found really attractive about the idea! Even between us, every single person that I spoke to when we were developing the project had such a very intense relationship to 90s cinema, but it was extremely different from one person to another.”

This personal connection many feel to 90s cinema is likely because of the incredibly personal stories that these filmmakers brought to the screen that captured the imaginations of a generation in flux.

“It was an extremely vibrant moment for global cinema in general. Part of it has to do with politics,” explains Bogutskaya. “Obviously with the Berlin Wall coming down, there’s new countries being born – especially after the fall of the Soviet Union and so on. So there’s huge political movements going on around the world that impact the way that artists and filmmakers are representing that world.”

“There’s a film screening as part of the season called Brat – Brother – which is a Russian film,” she says. “It’s extraordinary. It’s a reflection of the post-Soviet youth, and that could never have existed in any [other] moment…. Even La Haine, the French film with Vincent Cassel … they’re responses to political situations and how young people were relating to them.” Even beyond these politically-charged films, Bogutskaya highlights that “there is this very, very intense youthful energy” – the kind that ought to put the 90s back on the cinematic map.

Nineties: Young Cinema Rebels runs at BFI Southbank in London through July and August; bfi.org.uk