The rise & fall & rise again of attik

Few creative companies have experienced such extreme highs and lows as attik. It’s some story

In its 23-year existence, Attik has experienced some very high highs and some positively subterranean lows. It has gone from two people in a Huddersfield loft (hence the name) to, at its biggest, 160 staff in offices spread across three continents. And it has very nearly gone bust – several times. With so many design studios and creative companies currently experiencing their first recession, the tale of Attik’s rollercoaster ride will perhaps prove instructive.

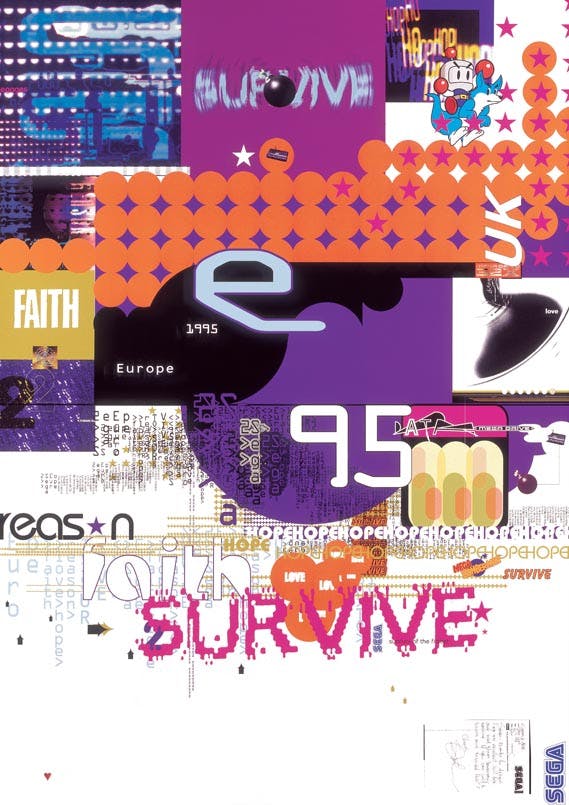

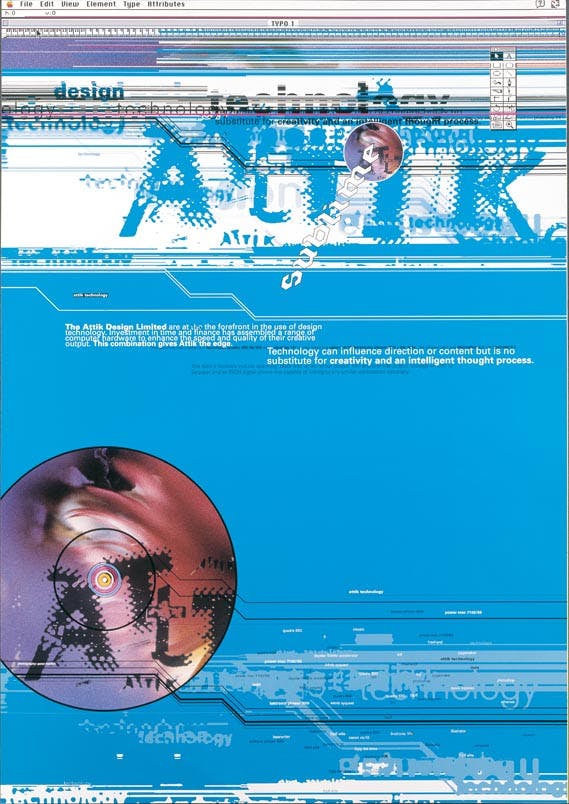

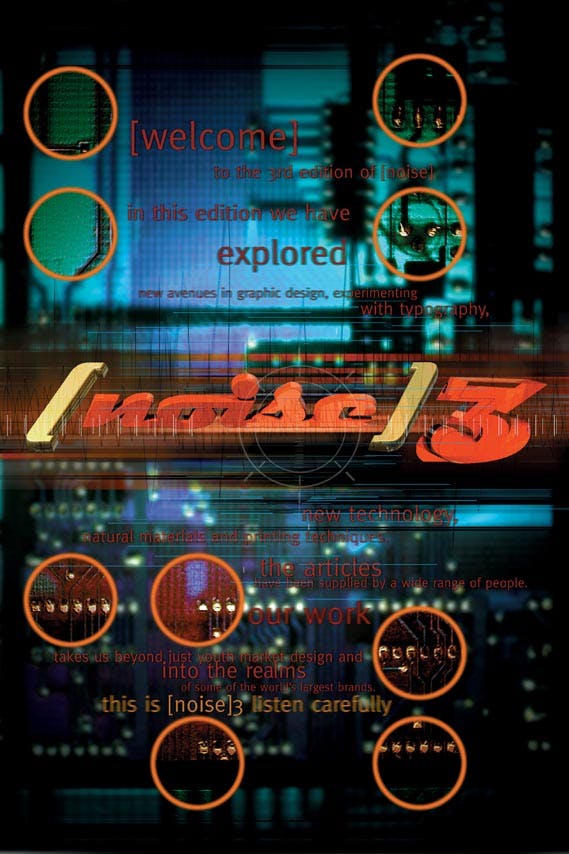

The story is documented in NoiseFive, the latest in the studio’s lavish self-promotional tomes. The original, Noise 1, was published in 1995 as an oversized colour broadsheet of just 200 copies. The following year came its sequel, Noise 2, expanded to 200 pages and boasting a pink flock wallpaper dust jacket. Seemingly a scrapbook of every prevailing graphic style of the age – a bit of Tomato-style distressed type, a dash of Designers Republic layering with a splash of Why Not’s typographic verve – the first two Noise books were not without their detractors, but nevertheless proved extremely popular and opened a lot of doors.

The Noise series, say Attik founders James Sommerville and Simon Needham in the latest book, “let us stretch ourselves and get the attention of bigger companies like national music labels, mtv London, Sony PlayStation, Nintendo. Ultimately, those two initial Noise experiments got clients to call us in, and it also caught the attention of young designers and artists, who saw the work and said ‘that’s the kind of work I want to do’. So we realised we had a new business tool and a recruitment vehicle all wrapped up in Noise.”

The pair had met at Batley Art College, aged 16. In 1986, two schemes born out of the 80s recession helped them get started in business – the Enterprise Allowance, a government scheme which paid £40 per week for 12 months to young people setting up a new venture, and The Prince’s Trust, Prince Charles’ organisation for young people which has provided funding for some 65,000 start-ups. The latter weighed in with £2,000.

Needham and Sommerville spent some of the money on a repro camera which they used to compose artwork in a top-floor garret in Sommerville’s grandmother’s terraced house in Paddock, Huddersfield. Their first job was creating leaflets for a second-hand clothing store called Gypsy Dress Agency, for which the entire bill, including the design, artwork, printing came to £70. “We thought that first year would just be an extension of college really,” says Sommerville. “It was all about learning stuff they didn’t teach you in the classroom, about how to get ahead in the real world. We’d advise any young person to throw themselves into it today if they have the belief and the balls to go for it.”

The attic became a rented studio in Huddersfield which housed their first Mac, an 8kHz Macintosh Plus with a whole four megabytes of ram. In 1989, they also began experimenting with Photoshop and TrueType fonts from an up-and-coming software company called Adobe.

In 1990, Attik posted annual net profits of £41,873, and had eight employees. Needham and Sommerville celebrated by buying a bmw each, which became the object of paint and acid attacks from somewhat unimpressed locals.

Boom was followed by near bust as, in 1991, the company experienced its first global recession and posted year-end losses of £14,000. The pair, now in their mid-20s, spoke to a lawyer who suggested giving it everything for three months to see if they could turn things around. Needham was making up to 50 calls a day, to anyone and everyone, to generate work. By mid-92 they once again had eight creatives on staff, including Will Travis who started on £6,000 a year. The turnaround was, in part, due to a conscious decision to target bigger firms and their client lists and try to undercut them; “It’s a chance to move into a space where you’d normally be shown the door,” says Sommerville. “Just bear in mind the (smart) smaller firms will be doing the same to you as they look up at your client list. It’s the commercial food chain.”

Attik started working for marketing services companies that had larger clients who needed design work. “I’d say ‘we’re a design company, but we can do any work you want us to do’,” says Needham. A firm would get a piece of business for someone and hand the graphics element to Attik. “For us it was a big piece of business. It meant I could go into clients and say ‘we did this’, and from their perspective they assumed we were working for that client directly. It was a really cheeky way of getting a lot further forward a lot quicker.”

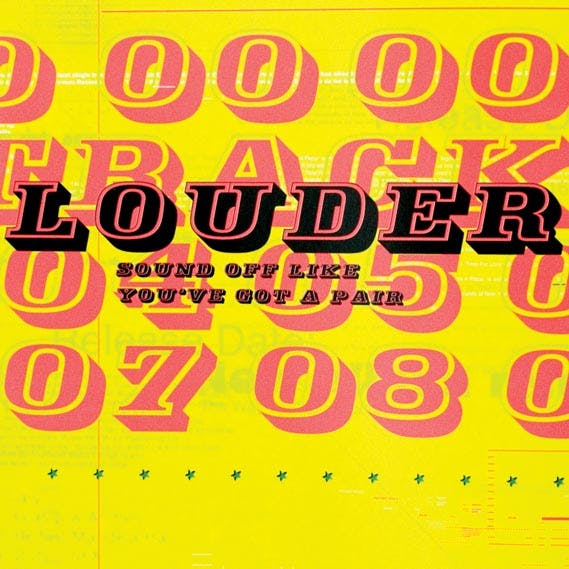

By early 1995 Attik had expanded the Huddersfield team to 25 people, largely as a result of Needham driving from Yorkshire to London, twice a week, in search of new business. A London office opened in 95 as Attik wound up producing 80 per cent of Sony’s packaging and point-of-purchase materials for PlayStation in Europe. In 1996, buoyed by the dotcom bubble, they decided to give New York a try.

Armed with just 24 sample copies of Noise 3 in a suitcase, Travis and Sommerville spent four days in back-to-back client meetings while offering Noise to bookshops on a sale-or-return basis. Back in Huddersfield, Travis worked daily from 9am till 4pm on UK new business and then from 4pm till 10pm on cold-calling companies in America, armed with the New York Yellow Pages.

Again Noise opened a door for them: an ad agency had seen one of the pages in Noise 2 and literally tore it out and presented it to Kodak. The agency offered to buy the page from Attik, whose response was “No, but we’ll create something original for you”. That became the first of 20 pieces that Attik created for the campaign.

Buoyed by a regular flow of such ad agency-derived work, Attik’s New York office opened on January 3, 1997. Sommerville went over to run it in 1998 while Travis opened a fourth office in San Francisco. Then the following year, Needham opened a fifth office in Sydney.

Needham says: “In the US and Australia, Attik found a niche doing work for all the top ad agencies that couldn’t do the work themselves. The agency cds and ads wanted some of the work we were doing applied to their campaigns, so we ended up doing really big projects for clients we wouldn’t have got access to otherwise. That happened consistently and was easy work to win because the agency creative teams spoke the same language as us. We rarely saw the actual client. But so what?”

This was at the height of the dotcom madness: “Everybody became king for a day, before the market crashed. We, and most other agency owners were offering $3–4k for a day’s work to some kid straight out of school,” Needham says.

Travis remembers a creative brought in from New York. “He arrived at the San Francisco office in a top-of-the-range Jag that he’d rented from Hertz. Then, I find out he’d gone over to Belvedere Island, which is the most expensive real estate in San Francisco, and was negotiating to rent a manor estate complete with gardens … just so his interactive team had a lawn to sit on while they dreamed up creative ideas…. Interns would walk in asking for $50–70k starting salary.”

By the end of 2000, the company was billing over $20 million, with more than 160 staff and studios in Huddersfield, London, New York, San Francisco and Sydney. But there was a major problem: Attik had built its business on projects and one-offs for other larger advertising agencies, not on work done directly for clients. With all of its work project-based, Attik was over-extended, working on too many short-term projects, constantly expending time, money and energy on winning new work.

“We had loads of people doing loads of projects and we seemed really busy, but commercially it was a total false sense of security. We weren’t really making sufficient profits to pay for our huge overhead at the time,” say Needham and Sommerville. “We’d basically spent 15 years grabbing hold of anything we could … we were continually cultivating two-month business plans, because you know a project will finish, and you don’t know whether that client will have another for you or not.”

Then the crash hit. In San Francisco, Attik went from considering leasing a building twice the size to taking on lodgers and charging them $1,000 per month to use a desk in the office. “We were easily $1 million in debt,” says Sommerville. The agency was bloated and had no long-term clients.

And then came 9/11. Every single agency budget went on hold, and Attik was too far down the food chain to speak with clients directly. “I remember [Simon], around September 13 on the phone to me,” says Sommerville. “He said, ‘I reckon we have to lose about 100 people in the next six to nine months’. Everyone was still in shock from 9/11, and we’re in New York with 50 people and there are 40 people in San Francisco and 50 plus back home in the UK.”

Although they needed to act quickly, the partners remembered how outside advice had helped ten years ago when they were last in serious trouble. Ric Peralta, Attik’s president today, first came across the company when he was in the process of selling his own agency, PrimoAngeli, to Cordiant. After a lunch in London with Sommerville, Peralta became a de facto board member. “I was someone to talk to, to get ideas from at that point,” he says. “I turned them onto respected lawyers, accountants, and bankers. It was simple stuff, you know, 15 minutes of my time here, 15 there, no big deal but probably saved them two months of pain.”

After half a year of this impromptu advice, Peralta was invited to Huddersfield to attend the July 3, 2002 Group Board Meeting. On the way, Peralta looked over the figures. “I’m on the train ride from London and it took all of half an hour to figure out they were in deep, deep shit,” Peralta says. “Their UK line of credit was maxed, and they were burning £50k a month. Revenue was nowhere near historical levels, and the backlog of work had disappeared. The cash that they had started the year with had been used up. My immediate question would have to be ‘how are they going to survive?’, let alone ‘how are they going to grow?’ When I strolled into their Huddersfield offices, there was the entire agency, who’d all flown in thinking they were doing a great job.

“One guy, the md from Huddersfield, gets up and does this half hour thing where he’s talking about the future and UK growth, blah blah blah, but I’d seen his numbers while passing through Doncaster. And I’m like, ‘Hey, let me introduce myself. I’m Ric, I’m one of the new board. Thanks for that, love the pretty pictures. However, you are talking shit and are not dealing with the reality of the past 12 months, none of you are. You have far too many staff, there are offices all over the place totally disjointed, the management structure is totally disengaged. Look, you’re a bunch of freelancers, running around all over the world, spending a lot of money, but you don’t own any part of your business. You’re subsidiaries, and it’s all so complicated that nobody that matters is touching the work.” Peralta finished by saying, “I want everyone to sit down and give me 20 names of people you’re going to fire tomorrow.”

Attik cut 115 staff, leaving just 45, with only Huddersfield and San Francisco operating fully. The Sydney and New York offices were closed. Partner salaries were cut by 30 per cent and frozen until further notice.

In San Francisco, the agency jettisoned a flock of Herman Miller Aeron chairs, a symbol of the dotcom bubble. “We went to the landlord of the building in San Francisco and said, ‘Hey, we don’t have the rent today, but we have these 12 chairs’,” says Peralta. “We worked it out because he had no other tenants to replace us. Exchanging chairs for rent gave us an extra month and in that time I’d worked out a renegotiation of the UK credit line, so we got through.”

Having been through a recession in 1992, Attik knew what to expect. In addition to a few remaining solid clients in the UK, the agency was continually hunting for business between 2002 and 2003. “We’d be calling up ‘old friends’ in the property sector, something we did in the early 90s in Leeds, so we knew their language,” says Needham. But ten years on, there were lots of younger studios that had emerged after the economic shake-up. “The UK was fiercely competitive. It’s like retiring from football and ten years later expecting to play against younger guys, it wasn’t the way to go.”

Focusing on long-term client relationships was the new strategy which bore fruit when, in 2003, the San Francisco office won Scion, Toyota’s new car aimed at a youth market. It was Attik’s first Agency of Record client, for which it provided branding, TV and cinema spots, print, interactive, events, guerrilla and viral advertising.

The UK operation had a more contentious saviour – Camel. The Huddersfield office called Sommerville in the US to see if it should take part in a pitch for the cigarette company. “It was tobacco and, apart from the fact nobody smoked, my dad had died of emphysema. I said, ‘you lot decide’,” says Sommerville. They declined to pitch. Camel then came back and offered a huge pitch fee which, in the dire circumstances of the time, rightly or wrongly outweighed moral obligations. “I thought what would my dad say, ‘sink or swim?’ So we pitched and won the business. Ironically, a tobacco company saved our lives.”

With a smaller, leaner team, Attik rebuilt its business. In 2004, Peralta and Travis were made partners. The following year, the Huddersfield office moved to Leeds, San Francisco was expanded and an Attik office opened in Los Angeles, and re-opened in New York, three years after closing last time. No agency contracts were accepted as the company focused only on direct client relationships and started pitching against the same agencies that it used to feed off. In 2007, with the likes of Coca-Cola, Adidas and Sony as clients, long-term security was assured as the company joined the Dentsu network.

Having started out as a print-based graphics studio and ended up as a multi-disciplinary ad agency-cum creative all rounder, Attik has rung the changes throughout its 23-year history. It’s gone from one room to five offices, back to two and up to four again. From two to 160 people and all points in between. As co-founder James Sommerville says in NoiseFive, “From where we began in Huddersfield to where we are today is our most successful project to date.”

The full Attik story can be found in NoiseFive, from which this text was adapted. Details of the publication can be found at noise.attik.com